Introduction

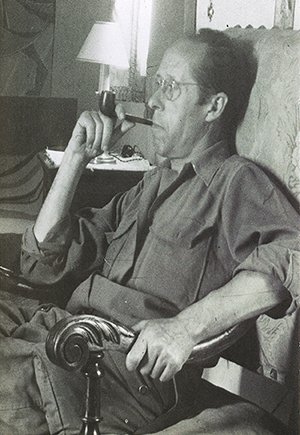

The work of André Breuillaud, still little known to the wider public, stands today as one of the most singular and coherent artistic paths of French modernity.

Over more than six decades, his painting moves from expressive figuration to a deeply personal organic language, in which forms seem to be born, grow and metamorphose within an autonomous pictorial space.

This trajectory—never governed by fashion—shows a rare fidelity to an exacting inner quest.

Origins and training: a sensibility shaped by nature, light and the discipline of craft (1898–1925)

Birth and rural environment

André Breuillaud was born on 17 July 1898 in Lizy-sur-Ourcq (Seine-et-Marne), a small rural town crossed by the Ourcq and its canal, surrounded by farmland.

This calm, horizontal landscape—structured by gentle lines and clear masses—formed his first relationship with the world.

He developed an early sensitivity:

- to variations of light,

- to the simplicity of natural forms,

- to balance between relief and expanse,

- to the silent presence of landscape.

This relationship with nature, far from the city, would durably inflect his work.

Mediterranean apprenticeship in Barcelona

As a teenager, he spent several years in Barcelona.

There he discovered another light: brighter, sharper, more contrasted.

The contrast between the softness of Seine-et-Marne and Mediterranean frontal intensity nourished a double sensibility:

- slow, deep observation of reality,

- an attraction to clear colour and cut-out forms.

École des Beaux-Arts in Paris: rigour, technique and independence

Back in France, he entered the École des Beaux-Arts, where he attended the studios of:

- Luc-Olivier Merson (discipline of looking, precision of drawing),

- Fernand Cormon (work on light and atmosphere),

- Paul Laurens (method, professional demands).

With Merson, he studied simple objects at length—eggs, bowls, leaves—in order to grasp their internal volumes.

This learning extends a “pedagogy of structure” that will be found throughout his organic painting.

With Laurens, he refused the Prix de Rome in order to preserve his creative freedom—an act that reveals his independent relationship to institutions.

1917–1920: rupture, service, maturation

Requisitioned in 1917, he returned to painting with an increased awareness of the world’s fragility.

This interlude marks the passage to a more grave, inward maturity.

Montmartre: humanity, expressive tension and the first structural investigations (1925–1936)

Rooted in the margins

Around 1925, Breuillaud settled in Montmartre. But he avoided the district’s artistic folklore:

he was drawn instead to transitional zones, wastelands, and social margins.

He painted anonymous figures, workers, ordinary gestures.

His painting is not documentary:

it expresses an inner truth through the treatment of masses, the tension of bodies and expressive modelling.

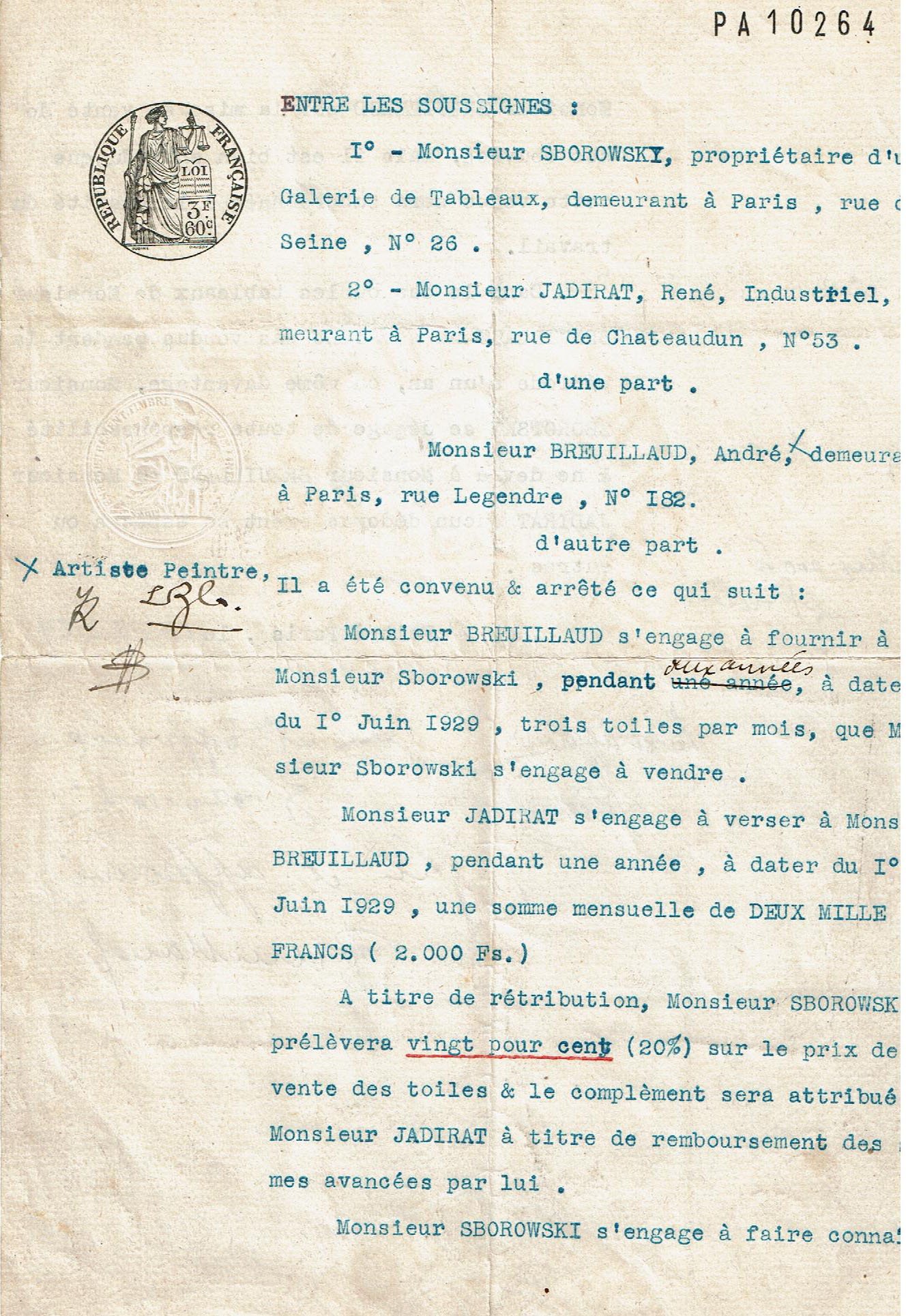

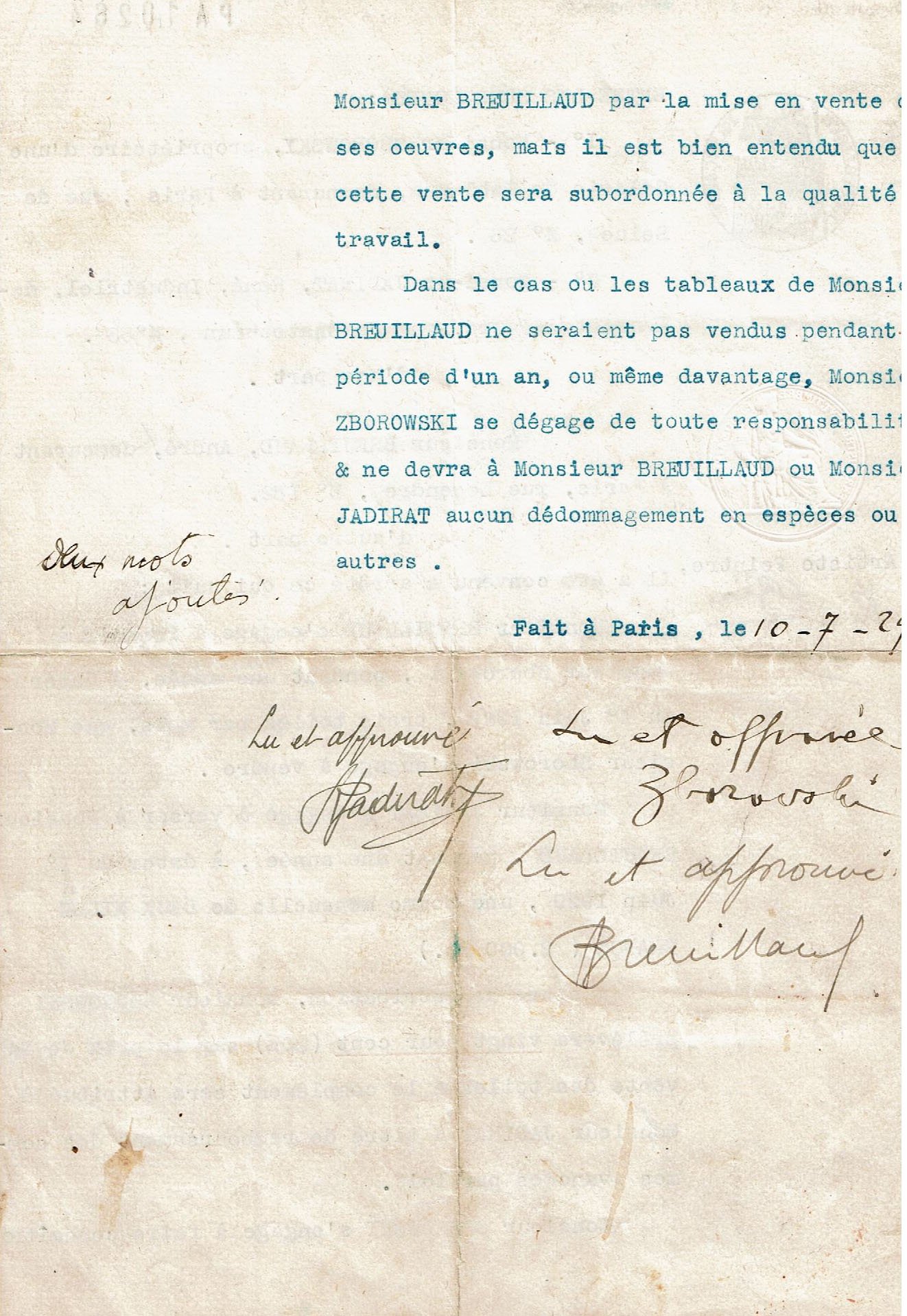

The encounter with Zborowski: a decisive moment

In 1929, Léopold Zborowski, a major dealer on the Paris scene, noticed a Montmartre landscape and signed him to a contract.

Zborowski recognised in Breuillaud:

Zborowski opened a gallery in 1926 at 26 rue de Seine in Paris, exhibiting contemporary artists such as Wanda Chełmońska, André Derain, Pinchus Krémègne, Chaïm Soutine, Marc Chagall, André Breuillaud, René Iché, Eugène Ebiche, Maurice Utrillo, Jean Aujame, Jean Fautrier, Alexander Mohr, Paul Welsch, John Graham, Hilaire Hiler…

- an authentic expressive force,

- a rare pictorial sincerity,

- an affinity of spirit with Soutine,

- an intuition for dynamic forms.

This recognition was brief—Zborowski died in 1932—but crucial.

Withdrawal, silence and transformation

After 1932, Breuillaud painted less for galleries and more for himself.

This forced withdrawal became a stage of deepening.

His painting tightened; compositions became more constructed:

he quietly prepared the transition toward a painting of structure.

Provence: space, construction, dry light — a laboratory of transformation (1946–1954)

In 1946, Breuillaud left Paris for Provence.

This geographical move marks a fundamental turning point in his work.

A geometric light

Provençal light, more vertical and drier, changed his approach to landscape.

Shadows became volumes; hills became architectonic masses; nature turned into a set of spatial forces.

From figuration to structure

Figures gradually disappeared.

Painting concentrated on:

- the balance of masses,

- the tension of planes,

- the simplification of forms,

- an analysis of reality as a system of forces.

He no longer painted the visible scene, but the framework of the world.

This period is essential because it directly prepares the emergence of the organic language:

nature became for him a model of structure rather than a subject.

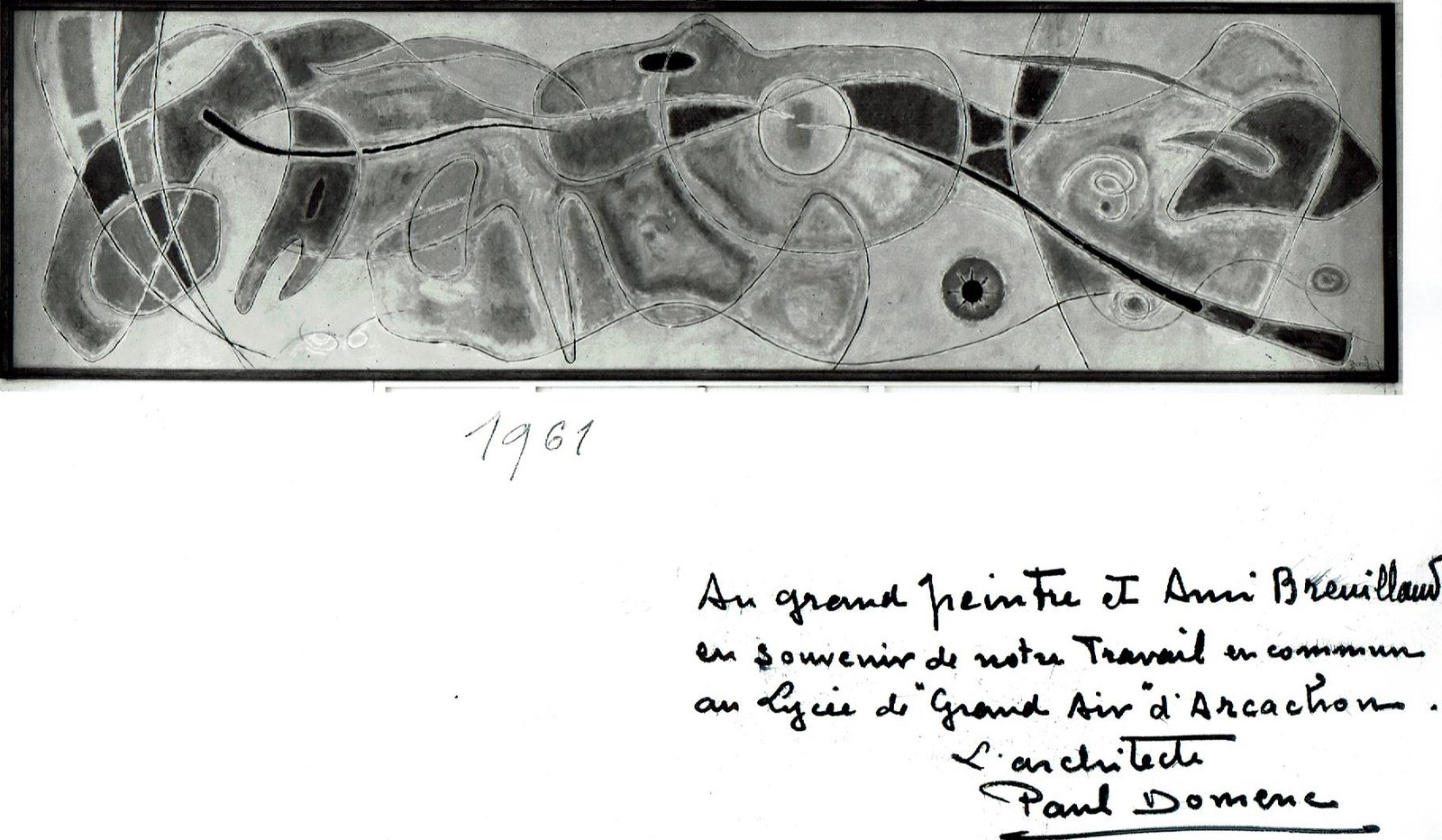

1955–1965: emergence of the inner world — the birth of biomorphy

A change of paradigm

From 1955 onward, Breuillaud gradually abandoned any reference to exterior landscape.

Forms now appeared from inside outward.

He invented a biomorphic language based on:

- membranous entities,

- expanding nuclei,

- internal filaments,

- semi-translucent masses,

- a matrix-like space.

Painting not the visible, but the origin

His paintings became sites of genesis:

they seem to depict the instant when form comes into being.

This shift must also be understood in a difficult personal context:

the illness of his wife Renée profoundly affected the artist.

The studio became a place of emotional transmutation—an inner survival.

Critical reception and singularity

In 1967, Georges Pillement wrote that Breuillaud “unfolds an imaginary biological universe which, by its inner power, joins the great visionaries of art history.”

He underlined the singularity of this approach, independent of all contemporary movements.

1966–1980: the apogee of the organic language — cosmic space

From 1966 onward, Breuillaud reached a form of total maturity.

His works now represent an autonomous space, without gravity, where form unfolds freely.

Features of the organic–cosmic style

- floating volumes,

- luminescent membranes,

- nodules of colour,

- energetic interactions,

- circular tensions,

- microcosms and macrocosms in resonance.

The artist explored what one might call the dramaturgy of the living.

The forms no longer arise from nature: they arise from within himself.

The 1970s: renewed intensity despite illness

Even as his eyesight declined and Parkinson’s appeared, the late works gained in clarity and softness.

Colour became atmospheric; form more spiritual.

This period bears witness to a rare mastery:

the energy of the living transforms into a luminous melancholy.

Importance and contemporary relevance

1. An exemplary coherence

Each period prepares the next—rarely does an œuvre offer such continuous evolution.

2. An anticipation of contemporary knowledge

Long before research on emergence, morphogenesis or living systems, Breuillaud was already painting forms generated by internal processes.

3. A modernity on the margins, but not minor

His distance from the market in no way diminishes the visionary force of his work.

4. A vast field still to explore

His work, largely held in private collections, remains to be explored, documented and exhibited.

5. A renewed pertinence

At a time when art engages with biology, ecology and the sensitive, Breuillaud appears as a precursor.